partners

partners

An Experiment in Collective Decision-making

James Moore - Curator-producer for Østfold Internasjonale Teater

06/06/2018

The Pig © KALEIDER - The Pig © KALEIDER

PIG is a playful experiment in collective decision-making that was conceived by the English artist Seth Honnor, Artistic Director of Kaleider. It is being co-produced as a Pilot Project within the framework of IN SITU ACT 2017–2020.

The laboratory for implementation is a public space where the common systems of societal controls are suspended. Money is the catalyst, while the pig offers a provocative invitation without any clear guidelines. Myriad factors will contribute to how the experiment plays out. Some of these will be consciously determined, while others will unavoidably be left to chance. Central to Honnor's hypothesis is an underlying premise of trust.

"This is a community fund. You may contribute to it if you like, and when you've agreed how to spend it, you can open me and spend it."

In essence, Honnor has designed and manufactured a large, transparent pig that will be positioned in a public space. Or, rather, into a series of public spaces throughout Europe. Standing atop a plinth, the plastic suid will be the size of a small car, measuring 2.2m long by 80cm wide by 1.7m high, with two slots on its sides for deposits. Installed inside the pig will be a scrolling LED sign stating, "This is a community fund. You may contribute to it if you like, and when you've agreed how to spend it, you can open me and spend it." In principle, all choices and actions beyond this are turned over to local inhabitants.

Furthermore, if the artist's intentions are honoured to the fullest, there will be no public announcements nor advance press. A simple listing of what (litterally), when and where in a program is acceptable, but nothing beyond essential information. Beyond the choices of placement and duration, there should be no mediation nor any form of authority exercised on behalf of the local presenter. The motivation is to genuinely invite the community to make decisions on its own terms, including how the community defines itself and who may represent it at any given moment.

Honnor explains that, "People, in my view, are generally good. What we do is we create systems to ensure that that is the case. When we remove the systems, then we get really scared that, somehow, people won't be good anymore. So what PIG is doing is really challenging those systems we've created to ensure that we're all really good, and do good stuff. Actually, what I'm doing is saying, 'Let's just trust that people want to look after each other. They don't want to fight. They actually want to come to consensus.'... We're removing the systems we've put in place to ensure people are good, and trusting that people will do something interesting. The generosity here is to trust people." [1]

Interestingly, in his brief history of humankind, Yuval Noah Harari describes money itself as a psychological construct based upon trust. The development of money "was a purely mental revolution. It involved the creation of a new inter-subjective reality that exists solely in people's shared imagination." This is sustainable because money is "a system of trust, and not just any system of mutual trust: money is the most universal and most efficient system of mutual trust ever devised." [2] Yet there is something dubious about placing cash into an unregulated, transparent container in full public view and trusting that meaningful good will become of it––without knowing who will finally decide to use it, nor to what end.

Ironically, "the pig is almost worldwide the symbol of gluttony and greed, gobbling up whatever is set before it. In many myths insatiability is attributed to it." [3] Piggy bank references aside, there is a wry humour at work when the pig becomes the vehicle for collective generosity.

Returning to the theme of trust, another nuance may come into play due to the relative anonymity and lack of instruction. Will the rather opaque nature of the gesture risk weakening its legitimacy? With community activities it is natural that the initiative-taker stand openly accountable. In this sense it may be argued that the transparent pig is anything but transparent. Will this inhibit the willingness of inhabitants to contribute to the pig? And yet, how can one take responsibility without becoming an authority, and thereby undermining the experiment? Honnor insists that his intention is not to hide. As he explains it, "My facilitation is to remove myself. Otherwise people will either lean on my authority or relinquish theirs. If I'm out of the way then I don’t contaminate their process." Will this create tension between the artist's intentions and the local presenter's sense of propriety? These are questions with which I have wrestled, and Honnor's position is that these reflections and conversations are equally part of the work.

This artistic intervention is not about the money. Honnor is emphatic that his interest lies in the questions, reflections and conversations that PIG provokes. The myriad dilemmas posed by the pig are the core of the work. The goal is to produce a space for meaningful engagement.

Of course, the obvious questions are whether anyone will choose to place money into the pig, and if any decisions will be made regarding how to spend it––whether by consensus, by vote, or otherwise. The money, if any is contributed, will likely become the immediate focus and object of discussion. But this artistic intervention is not about the money. Honnor is emphatic that his interest lies in the questions, reflections and conversations that PIG provokes. The myriad dilemmas posed by the pig are the core of the work. The goal is to produce a space for meaningful engagement.

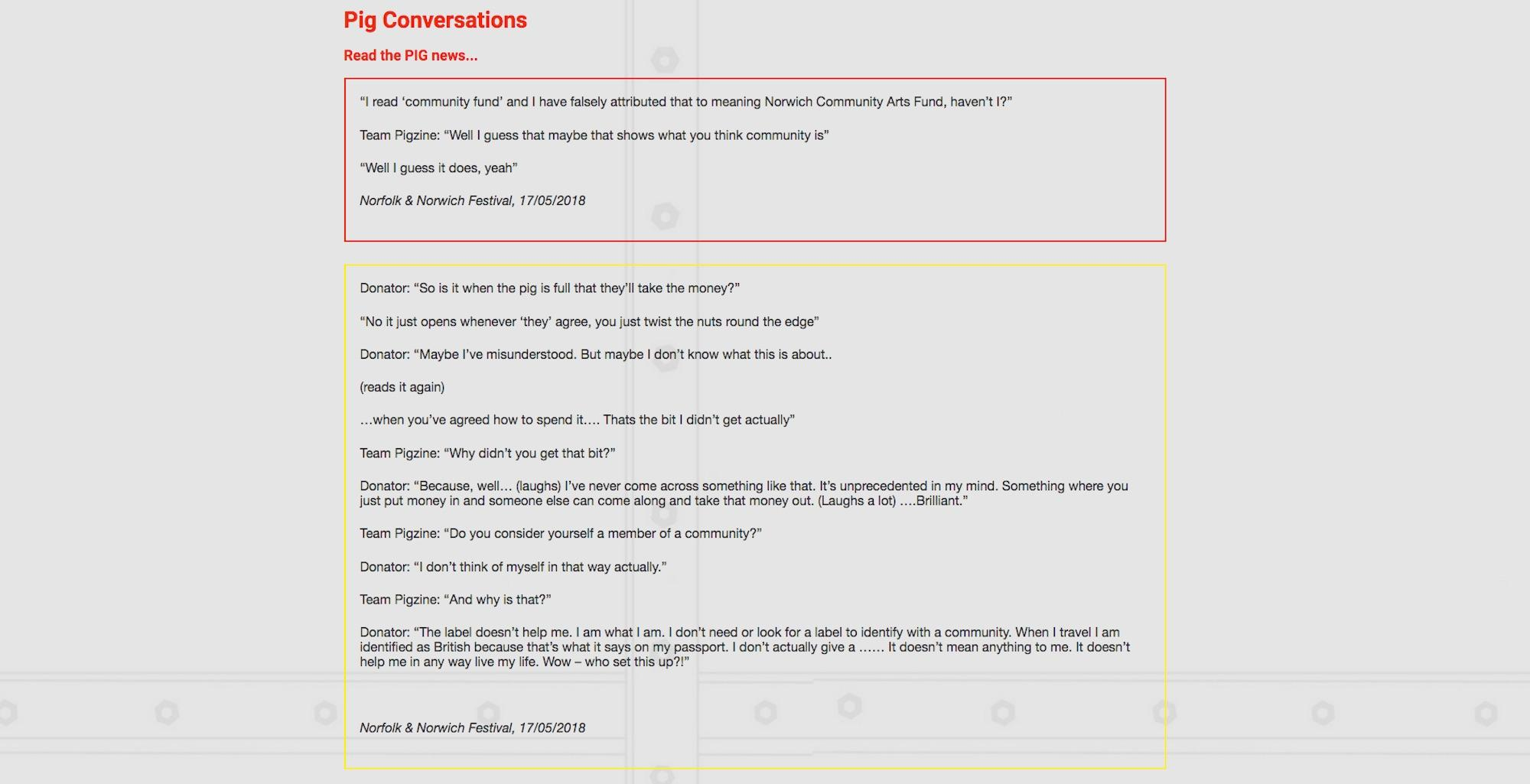

Conversations around the pig (Printscreen from www.pigzine.com)

Conversations around the pig (Printscreen from www.pigzine.com)

When it comes to implementation, PIG poses a series of challenges and concerns for the curator-producer. Some choices are of a practical character, while others may significantly impact how the experiment will play itself out. During an intensive, two and a half day visit in February, Honnor and I engaged in a series of conversations and meetings, many together with local partners and inhabitants in the Norwegian towns of Moss and Fredrikstad.

The selection of the site is critical, as the placement of the pig will influence not only how and where it is seen, but also how it may be engaged. It is important to identify sites of perceived neutrality. If we are to genuinely turn over authority to the community, then we need to avoid any sense of ownership, even if only by association or proximity. It is also important that site allow for reflected engagement and conversation, a space that amounts to an eddy in the flow of urban movements.

A pragmatic consideration was whether or not to offer alternatives to cash contributions. Cash is disappearing from the Norwegian economy, as physical money is becoming an anachronism. Orwellian concerns aside, should we explore options for card or phone payments? How would we visualize how much money is in the pig if you cannot see it? How do you ensure the cash will be readily available the moment the pig is opened (whether once or several times during its stay)? How might any of these alternatives be facilitated without the agent becoming a de facto authority? Does it enhance or detract from the experiment if people have to go somewhere to acquire cash in order to contribute? How critical is it that there is (a lot of) cash inside the pig for the artwork to engage the community?

A different concern is that there is little tradition for charity with money in Norway. Charity though labour (dugnad) is more common, even if this civic character has weakened during recent years. But the socialist underpinnings of the state and generous public financing have distanced citizens and residents from the personal responsibility for economically nourishing local resources and activities. This stands in stark contrast to the United States (where I grew up). Some may feel alienated, untrusting, or indifferent when confronted by this proposal. This does not lessen the relevance of the experiment, but its significance as a contextual factor cannot be understated.

For our local manifestation in Moss we will present PIG in cooperation with Christian Fredrik Days. Christian Fredrik was a Danish prince who was to be king of Norway following the Napoleonic wars. Denmark, having sided with France, was obliged to give Norway to Sweden as the spoils of war following several centuries of Danish rule over Norway. But the Norwegians wanted to become a sovereign state. Sweden was not amused by this and amassed its forces to bring about submission. Christian Fredrik, who was quite young at the time, negotiated a peaceful settlement whereby Norway could establish its own constitution and parliament, enabling self-rule domestically, while being represented in all international matters by the Crown of Sweden. The negotiations for this occurred in Moss in 1814, laying the foundations for the modern nation of Norway, which achieved full sovereignty in 1905. Christian Fredrik Days is therefore a celebration of peace, freedom, and democracy. Placing PIG into this local context––though unannounced in the program––will frame the experiment in a setting where reflections upon self-governance are palpable.

Having addressed the issues in advance of PIG's arrival, how shall we then follow the reactions, discourses, and activity relating to the pig once it is in situ? How may we discretely observe and document activity in a manner that does not overtly influence it? Put another way, how may we harvest the fruits of the investigation and learn something of value? Something that will contribute to our understanding both of our local community, and of our ongoing enterprise of artistic creation in, about, and of public space?

This last point also builds a bridge from the local to the European. As we follow the journey of PIG through a variety of social and cultural contexts across Europe, an unscripted narrative will emerge that will address some of the questions above while raising new ones along the way. Even if this narrative comprises but snapshots, it will nonetheless enable a secondary set of reflections and broaden our discourse about artistic interventions in the public realm.

[1] Seth Honnor during a conversation with local partners (Moss, Norway 2018)

[2] Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens – A Brief History of Humankind (Vintage, London 2014) pp. 197–201.

[3] Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt, A Dictionary of Symbols (Blackwell, Oxford 1994, translated by John Buchanan-Brown) p 753.