artists

artists

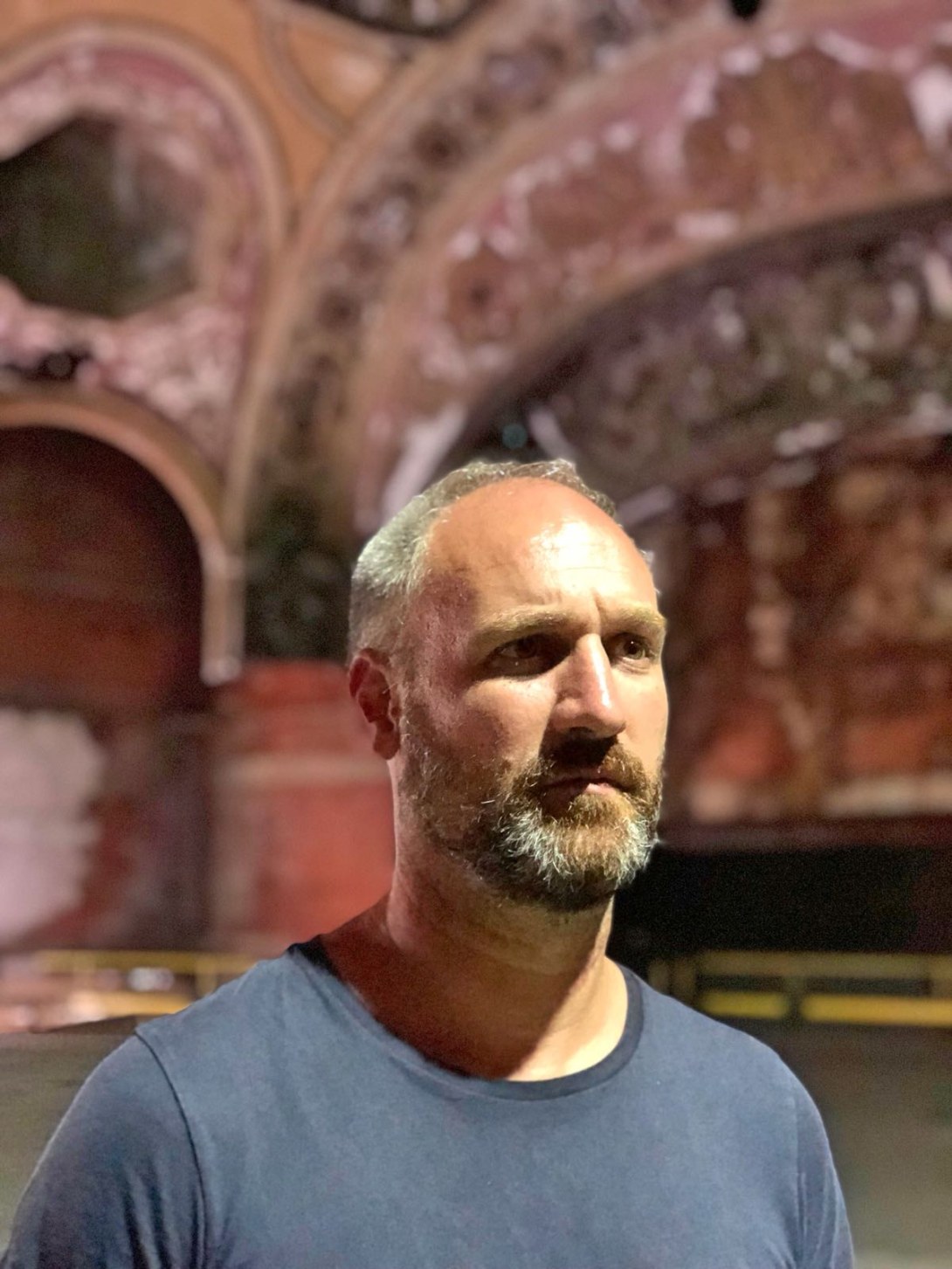

Sauf le Dimanche meets Matthias Tronqual

[EN] An interview between a collective and a programmer

16/05/2024

Emilie Buestel and Marie Doiret are the Associate Artists of the Scène Nationale de l’Essonne within the (UN)COMMON SPACES project. They were invited by former director Christophe Blandin-Estournet. Having retired midway through the project, Matthias Tronqual replaced him

Seizing the existence of IN SITU Narratives as an opportunity to meet further, Emilie, Marie and Matthias meet for a three-way conversation, giving birth to an IN SITU podcast episode in French. These questions seek to bring into dialogue the vision of the programmer and that of the artist, around creation in public spaces and non-dedicated spaces. Their bias is to try to discuss from a sensitive, intimate, personal point of view, daring to express their tastes, daring to say what inspires them in creation and programming but also as an audience.

| Sauf le Dimanche (Emilie) When you programme shows for your theatre that are going to take place in an outside space, do you programme a specific work or do you go out and find a place and a context which you will set work to? |

Matthias Tronqual [...] I'm more interested in programming works that are about or echo local issues. But to be able to programme these shows and understand the issues involved, you have to work in a partnership beforehand, co-constructing projects, meeting with partners and getting to grips with the social, political and cultural issues in the local area. So at first glance, I'd say that these days at least, I make more of a distinction between a theatre space and a public space. That's because, for me, both the theatre and the public space are places where issues get addressed. They're addressed in different ways of course, but they're all issues from this local area, and I think that's important. And above all, I think it's also after being greatly facilitated by working with the Scène Nationale [de l'Essonne], having worked in the public space, having been able to focus and confront these kinds of issues. Particularly [these issues]: the question of the body in the public space, the role of women in building social links and young people's stories, which I see as the key issues in the local area. | |

Sauf le Dimanche (Marie) And here's a question that ties in with Emilie's question: in our experience, as artists working on projects outdoors; in non-performance spaces, in public spaces, there's this feeling that dialogue about the work between the programmer and the artist is more intimate, more precise, more transparent. There's a feeling of working together to find the right context, and that this might somehow be less true of conventional stage programming. Is this a misconception or do you feel this way too? Matthias Tronqual I think there's an unknown aspect in the response to a live performance. I think a lot of programmers take the fact that they're in a theatre for granted, assuming that the show will automatically go over well. You can't get that when public space. The public space confronts us directly with how the work will go across, and so we need to consider all the issues involved, and talk about them with the artists before we even start programming, or while we're programming. This is a real asset in my eyes. It takes nothing away from the work. It's the opposite in fact – it actually increases the richness of its reception, and the different possibilities of how this work goes across. That's because it's in the public space, because the intention prerequisites aren't the same; they're not codified and you have to create the context for how the work goes across yourself. And that's a completely integral, conscious decision from artists performing in the public space. Sauf le Dimanche (Emilie) How would you answer that question, Marie? When a programmer schedules one of our shows in a non-performance venue, does that mean more preparation is needed? What kind of relationship does that require with the programmer, with the location we're going to be performing in? Sauf le Dimanche (Marie) Even if the programmer has seen the show, I think the fact that we have to project it together in a context and in front of people who are suddenly embodied in our imaginations as programmer and artist means we still have to talk about it together, even if the programmer has seen the show. How it's made, why it's made the way it is, what the intention is in the relationship between the sender and receiver... |

| Sauf le dimanche (Emilie) Marie, what are you sensitive to as a spectator? |

Sauf le dimanche (Marie) Hmm. So I may be a dancer, but first off, I think the thing I like most is to be told stories. I love stories, I love narrative and I love fiction in fact. I'm also an avid reader. I'm also a cinema-goer for that very reason, I think. I worship stories. And after all, as a dancer who's somewhat initiated, e.g. capable of analysis, I'm still amazed every time I have the opportunity to discover a new choreographic language. I'm always amazed to see a body dancing a dance I don't know, a dance I've never experienced, a dance I've never felt. It still fascinates me. But it fascinates me in the same way as the first ever dance shows I saw, which probably got me into dancing in the first place. And lastly, I'm also a spectator. So, every time I see a show, I quickly start noticing how certain performers catch my eye and not others. That's another thing I love doing as a spectator. I love asking myself why, in this particular format, being viewed by 300 other people around me, why is that particular performer burning with a fire that I can't define, that I can't explain and that keeps my gaze constantly returning to them? I love the mystery of that, that's definitely something else I love. Sauf le dimanche (Emilie) How about you Matthias? Matthias Tronqual What am I sensitive to in a show? First of all, the imagery, because that's the first thing we see, often even before the text. And when I say imagery, I also mean the body and the actual presence of an actor, a dancer or a circus performer. And I think what's magnificent about live performance is exactly the idea that the body, the visual presence, the sensory presence kicks in before the rational presence, and this is something that's intimate, subjective – it's how you get in. This doesn't mean that you'll like a show, but you'll always be drawn to a show by a performance or visual codes that you find interesting. That's not true of everything, because we can even be visually turned off from the outset by something that we didn't like. But I think you have to accept the primacy of the sensitive and particularly the visual, even before you know that you're going to get into a show and enjoy it. Sauf le dimanche (Marie) And you Emilie? Sauf le dimanche (Emilie) I'm going to put it a little differently, but I think it's all along the same lines. For me, going to a show really takes me back to the mysteries of life, things we don't understand, things that lie beneath the surface. It also takes me back to otherness, to discovering things I would never have imagined. And I love the communal experience too. Being together, watching this together, applauding, that's what it's all about. I think that's very powerful. |

| Sauf le dimanche (Marie) How do you make your theatre accessible to everyone? Is the theatre a communal space? As in, everyone is invited? And, forgive the truly awful expression, what does it mean to "reach audiences"? |

Matthias Tronqual I think the reason we often use the expression "how do you make theatre accessible to everyone" is because we probably see them as closed places. As professionals, we really need to work on this idea or this representation. What makes a theatre closed? I have two answers to that anyway. So firstly, what makes it accessible again and secondly, what makes it closed? It's closed for a reason, because it's a location, a place. I don't like this expression, but it's a 'safe place', i.e. a place where you can create a theatrical performance outside of everyday space, and public space for that matter. It's a place where we can use something sensory to capture people, capture their gaze, capture their attention and transport them into their own imagination, without there actually being any confrontation or violence. I mean the violence that is commonplace, the violence of everyday life in all places and encounters and so on. So you could say it's closed in the sense that it preserves a space for encounters, a space where the imagination can unfold. However, it's important that this preservation doesn't prevent certain people from coming. So to prevent this from happening, we've got work to do. And that goes back to the first question we asked, i.e. what ensures that there is a place for everyone at the theatre? Personally, I think there is a place for everyone at the theatre if the theatre is the public space for the imagination, and if we can ensure that a local area's major issues can be addressed creatively and politically within the theatre space or within the symbolic spaces that a theatre deploys in a territory. And that's how we keep things open, accessible. Open in the sense that everyone has a place there. So you have to first do an in-depth analysis of the local area, This means working structurally on partnerships and the co-construction of the theatre project before you even start on building audiences. Or before you go onto even the next stage, which is the tail end of the comet as well as the last job, the end of the chain, which is going out to find audiences based on a proposal. But 95% of the work is done beforehand, even before the programming happens. I'd say the rest follows on naturally on its own. Sauf le dimanche (Marie) While discussing these issues with Emilie, it reminded me that, as a company, we were also saying – and this is not very fashionable and I'm afraid it's becoming less and less so – that there's also a joint decision to be made by companies and programmers: we need to agree that it's not about one good turn deserving another when you move from inside a theatre to an outdoors performance. There's a logic about profits and accounting that might make sense on the surface; one which says, "you can perform outside if it brings a new audience back into theatres" but that logic is something that we feel is a lost cause in advance. As such, we believe that we should all agree jointly on the fact that performing outside has value in itself, that you're experiencing something new here, an encounter between a play and people. Matthias Tronqual I actually think that's a completely outdated vision. Also, it would mean that the shows performed in the public space would be more accessible and therefore perhaps less artistic and less rigorous than any performed in a theatre. And I think we need to combat that. But at the same time, we have to fight to show that there's no such thing as certain artistic proposals being central to audience development strategies while others are more cutting-edge proposals that only a few people can access. I think it's more the public space and what's offered in the public space that has changed the way we look at what urban theatre should be today, as opposed to the public space and what's offered in the public space becoming a means of getting people into theatre. I think that's really the situation we're in today. It's a paradigm shift that we need to make. And it'll be through exploring and experimenting with these new aesthetics in the public space. |

© Association des Scènes Nationales © Association des Scènes Nationales | « I think there is a place for everyone at the theatre if the theatre is the public space for the imagination [...], and if we can ensure that a local area's major issues can be addressed creatively and politically within the theatre space or within the symbolic spaces that a theatre deploys in a territory. And that's how we keep things open, accessible.» Matthias Tronqual | |

| Sauf le dimanche (Marie) Matthias, we have a question for the little onboard camera in your mind: when you've just programmed a show and it's one you've decided you want to show people, what happens at that exact point where people are watching it? What's going through your mind at this precise moment? What are you seeing? What are you feeling? |

Matthias Tronqual Exactly the same thing that happens just before I decide to programme a show, which is a huge responsibility. It's a very delicate period for someone running a theatre. It's when you realise that you have a responsibility and that you're committing audiences to artists and artists to audiences in a two-way process. I ask myself a lot of questions. It's a hugely vulnerable time because it's when you finally see the responses; responses that you've perhaps slightly predicted, or even bits where you've had to tell yourself "this has got to work", which is such a lizard-brain response. It's a sense of "this has got to work, people have got to be happy with what they're seeing." And at the same time, you're always constructively criticising. You have also got to tell yourself to accept that this encounter may not happen. It's a difficult time but it's necessary. It's cathartic every time when you actually work out what's happening in the room. Sometimes it's joyful, sometimes it's extraordinary. And then there are times when it's a deep and serious responsibility because you suddenly realise that you're going to have to work on what just happened. And you also have to figure out how. But you can totally feel all that in the room. You instantly get the complete response when you're in the room. So that's a time which comes with obligations, in a way.Sauf le dimanche (Marie) Emilie, so you're choreographing plays that will be performed for audiences. And because I write with you, I know that, as part of your creative process, this audience you haven't yet met already exists for you. You're obviously thinking of the audience because you're writing the show for them. So, let's talk about the exact point where you, or the show you've written for an audience, come together and meet. What is going on internally in this moment? Sauf le dimanche (Émilie) Just like Matthias said, it's a very vulnerable time... The special thing about it is that you can fully see the audience when you're dancing in the show, and there's something about that which makes you really embrace it, you've got to be 100% yourself. I've rediscovered that experience of going out on stage there, with a group of amateurs. I find that the stage is a really powerful way of going on a journey. And when you're in a classroom, there's no lighting, no costumes, no make-up, you're not hiding behind anything. So there's something that you have to tap into very deeply. You have to be really committed... It's a real experience. So when you're developing a play and you're thinking about the audience, does that influence what you create? What influence does the audience have, even before you start dancing in front of them?Sauf le dimanche (Marie) It's a huge question because I'm not sure I can answer it. I think it's a very unconscious thing, because what stands out for me, in the relationship with the spectator, as the performance is happening and you're not on the stage and the audience isn't plunged into darkness, is that thing you learn and you formulate, that you try to pass onto the performers and which isn't really very self-evident – that, as performers, we must avoid prejudice. It all comes back to the response thing, which, you're right, is something which is unspoken in every way. And that applies however deep the artistic side of things goes, i.e. you can very quickly judge the body, the gaze of the spectator watching you dance. However, what they're going through and feeling belongs to them entirely, and them alone. And so I think that is the main thing that stands out for me in my 20 years of experience. It's really the need to keep reminding ourselves, like a mantra, that we can't prejudice anything specifically in the response, and that it's important. |

© Jonay P Matos © Jonay P Matos | "It's a very vulnerable time... The special thing about it is that you can fully see the audience when you're dancing in the show, and there's something about that which makes you really embrace it, you've got to be 100% yourself. I've rediscovered that experience of going out on stage there, with a group of amateurs. I find that the stage is a really powerful way of going on a journey. And when you're in a classroom, there's no lighting, no costumes, no make-up, you're not hiding behind anything. So there's something that you have to tap into very deeply. You have to be really committed... It's a real experience." Émilie Buestel, Sauf le dimanche |

| Sauf le dimanche (Emilie) Does the theatre itself, from a venue point of view, still have meaning? Should we create new venues? And since street arts very much have become an integral part of festivals, is this still relevant today? Is there any point to inventing new ways for audiences to receive the work? |

Matthias Tronqual I think that the theatre as a physical place still has meaning even today. I think there is a lack of peaceful spaces, of encounters where we get people together to confront major issues, whatever differences there are between us. Also, we're in a period where political ideologies are in a state of extreme flux, much like religions, which are also in a different place, a place where we are also questioning the meaning of collectivity and why we are together. Well in this context, art is also extremely fragmented, or in any case it's being re-examined. At a time like this, these places of poetry are needed more than ever. I would even say, considering all our ecological and environmental challenges, they're even more important than ever. This is because I feel that environmental degradation is an exact echo of an end or decrease in lyrical richness. And the less poetry there is, the less richness and biodiversity there will be. So I think that, in the same way, if the theatre is doing this, festivals are also finding their own ways and means of doing this. Therefore, I'd definitely say that this place or these places in any case, have to survive because they're needed. And I think it's also a question of forms as well as society, and the times. At different times, you're going to encounter forms that will sometimes be more relevant, and sometimes less relevant to that time. I think there's still work to be done here in understanding how that works. We need to think about how these forms of encounters should work in terms of space and the era, and perhaps in a slightly different way too. But I think that festivals are thinking about this a lot, they're burgeoning, even if there aren't yet any models that are extremely relevant to our society. And I think that at the moment there's a real debate going on in theatres to ensure that these new forms of encounters are also able to exist. So I'm quite reassured and confident about this. The only question is, how much time will we have to experiment with this? Sauf le dimanche (Emilie) How about you, Marie? Sauf le dimanche (Marie) When I listen to Mathias, it has me thinking. There's a text by Lagarce that begins with "We must preserve the places of thought, of the imaginary, the places where this luxury is sustained". I think he uses the word "luxury" and I like that. "Luxury" which actually means these spaces are the most threatened in our extremely contemporary world. And yes, I couldn't put it any better than Matthias. Basically, when the theatre space is somewhere that reminds us that this is a fundamental human need, and part of how human groups are constructed, where we share metaphors and the unknown; when it's a space where we consider the things we don't understand, the things we don't know but which pass through us, which have an impact on us, and when these places have a commonality, then yes, this space is still absolutely essential. And this is even after we've had an era of forms and formats, and we've seen that there's a regular need for the system to undergo restructuring and a reconsideration of its prerequisites. Even after all this, it still remains a vital and necessary movement. So yes, yes, of course, they're places we have to cherish. |

« I'm a great believer in diversity, [...] I think we absolutely need diversity, diversity with groups of people, diversity in intentions, diversity in the use of our shared spaces, both symbolically and in practice. Places of learning need to be places of creation, places of creation need to be places of care, places of care need to be places of learning... and that includes for women. That actually means we have to be in this experience together » Marie Doiret, Sauf le dimanche |  © Jonay P Matos © Jonay P Matos | |

| Sauf le dimanche (Emilie) What do we need today, and what do you believe in today? |

Matthias Tronqual So I wouldn't have given you this answer yesterday or the day before, in any case, not at the beginning of the week. But what do we need today? What we need is trust and experimentation. I think we're in a society where we no longer trust anything, where we don't trust others. That now forces us to ask the other person what the final destination is before we even act, just because we no longer have any trust. We want to be clear about the intentions before taking action. And this is clearly also the case in France, because in France we have an extremely rational approach to things and when it comes to emotion, this is often relegated, even neglected or undervalued. And I think that this part of the unknown, this part of "we don't know where we're going, but we want to do it", well if there's no trust with that, then we're screwed. And this also fits in perfectly with an extremely capitalist approach that forces us to set objectives before we even try out things. So I think that if there's no trust, there's no experimentation. And I think that today, in a society where we are effectively being asked to perform, to get on track, etc, then if we don't accept failure today, if we don't make a place for lab work and for experimentation to happen, then paradoxically, failure is exactly where we're headed. So I believe in the necessity for trust. That's the first thing that's going to get us back on track. It's because trust means being able to imagine a future straightaway. It means the possibility of that future existing, that it even takes precedence over the present as well as the possibility of thinking about and imagining what will happen next. So that's the only thing I believe in. And I believe that our theatres and venues are places for experimentation because they tend to trust the people who come to these places and the artists they work with. And that, for me, is perhaps a glimmer of hope for the future. Sauf le dimanche (Marie) What do you believe in, Emilie? Sauf le dimanche (Emilie) I think what I'm about to say will back up what you're saying. I'm also a great believer in the power of doing, in experience, and that's what I believe in as an artist too. I'm also a great believer in collaboration, in breaking down barriers, in getting different venues to open up and do things together. Places that haven't necessarily known how to work together basically starting to collaborate. Breaking down barriers. Sauf le dimanche (Marie) I'm a great believer in diversity, but in the end, it ties in with everything you're saying. I think we absolutely need diversity, diversity with groups of people, diversity in intentions, diversity in the use of our shared spaces, both symbolically and in practice. Places of learning need to be places of creation, places of creation need to be places of care, places of care need to be places of learning... and that includes for women. That actually means we have to be in this experience together. | |