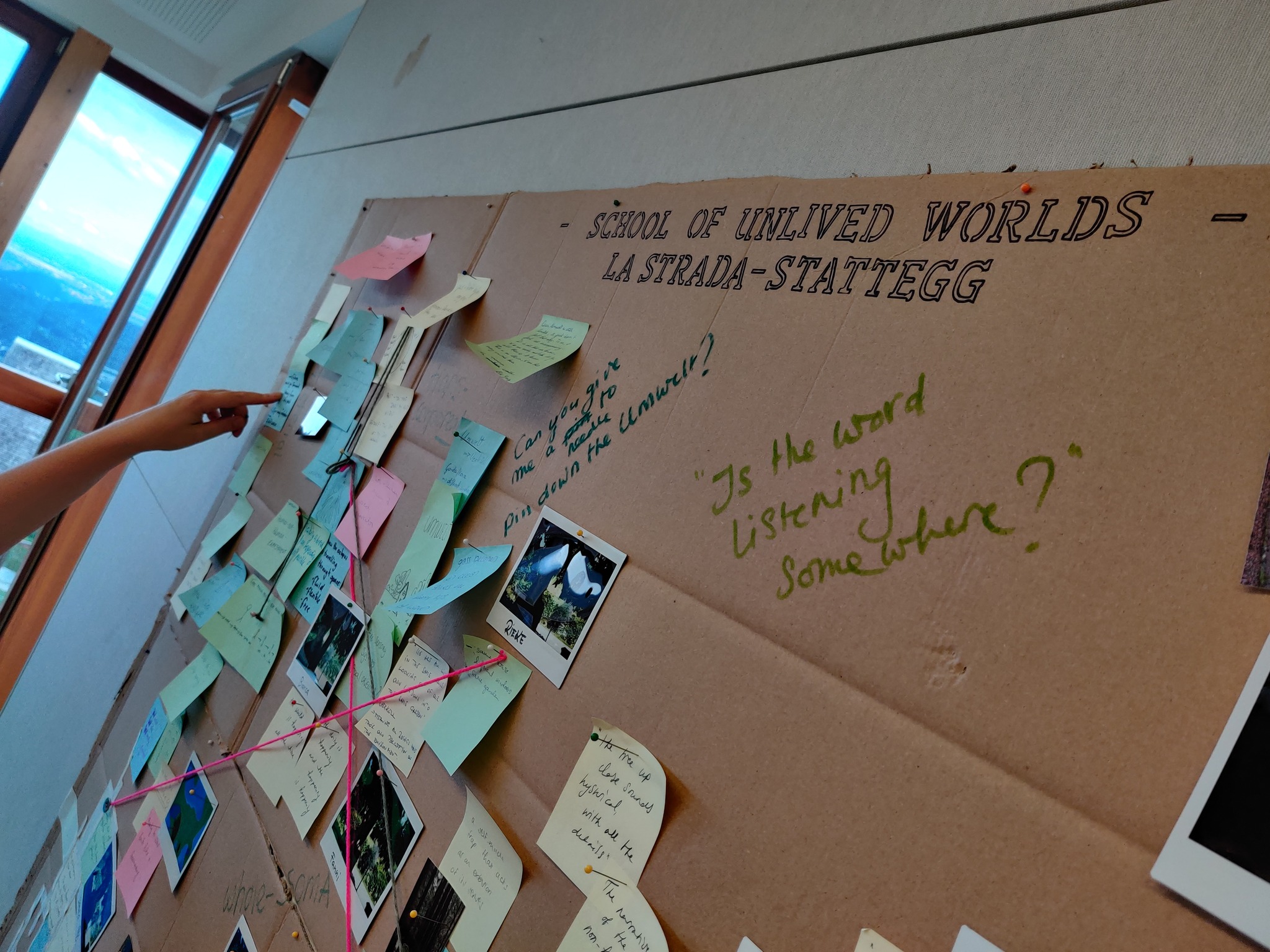

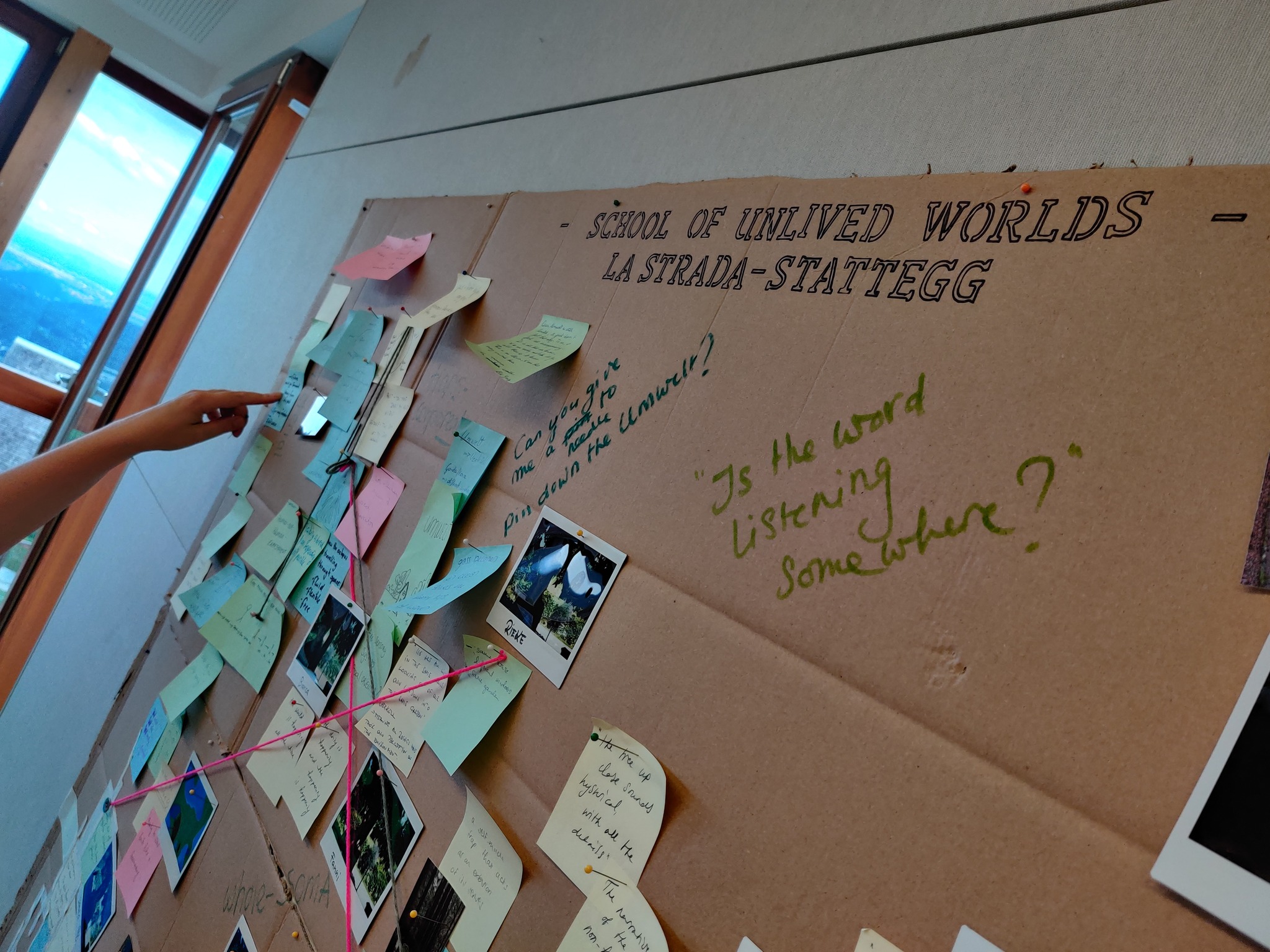

She embarked on a trip that shows her how relative her normal experience of the world was. Based on this experience and her interest in the workings of the human senses and psyche, she is now developing a project called ‘The School of Unlived Worlds’. In it, you, the audience, are asked to place your 'perception bubble' amidst the perception bubbles of other people and other animals and to try creating new bubbles (‘Unlived Worlds'). This fosters a deep respect for the worlds of others (including those who aren’t human) and a sense of the wonderfulness of existence. This text describes her initial experience as an example of the workings and mindset behind "The School of Unlived Worlds"

The octopus exercise

It seemed like no one was there. I took one last good look around and then left the path. With brisk steps, I walked into the forest until I guessed there were enough trees behind me to make me invisible. This was the part that I wasn’t actually allowed to go into. If someone discovered me, they would not only catch me doing something strange, but also something illegal. For the same reason, the chances of me running into someone there were also fortunately slim.

In the shelter of a large oak tree, I sank down until my hands and my knees touched the ground. My right knee dug into something sharp, a pebble. I moved it a few centimetres, and set it down more carefully. Under my hands I could feel wet moss, leaves, a twig. The deep, pungent smell of the earth was heady here. I looked around me one more time. There was nobody. I set my alarm for an hour’s time. |

|

|

|

| When I had been writing, I’d been completely bogged down in my thoughts. I had hoped a change of scenery would help me and had gone to my parents’ attic room to work. But even there, my mind stagnated. After a lot of staring, pondering and an extraordinary amount of procrastination, I decided it couldn’t go on like this. I devised a plan. I decided to do something I had never done before, in the forest, because I hadn’t been outside much lately. What I was going to do exactly, I didn’t know yet. The suspense would at least put my senses on alert and distract me from obsessing over that stupid text. It had to be something physical, something that would at least make me fully present, in my body.

|

Then it hit me: I would crawl through the forest on my hands and knees for an hour. It was so weird that I was sure it would take me right out of my "normal" brain. I forbade myself to go back on my resolution.

|

Meanwhile, I dreamt up all kinds of excuses for if someone caught me, such as a lost contact lens, research about the forest floor for my studies, seeing something shiny, but it turning out to be nothing

It was raining a little so hopefully not many people would be around. |

| Only when I had been on my hands and knees in the forest for a while did I really start looking around. The trees weren’t very dense here, which meant there was a lot of life on every level. There were bushes, moss, small mushrooms on branches that had been blown down in the wind, grass, birches. |  |

| I had a crick in my neck, and when I relaxed it, I automatically looked down. It was helpful seeing where I could place my hands but I also wanted to be able to see around me if somebody caught me. I tilted my head to listen for people. Still nobody. Then I moved my hands and knees about ten centimetres forward. |

My knees turned out to be a bit sensitive. I noticed every twig, bump and pebble. With my hands, I could feel the stems of leaves, their veins, their edges. I sank into the soggy moss and found the firmness underneath. Every step was a sensation, and the ground had a response to every movement. It’s a conversation between two bodies. It’s crazy how I normally think of the ground mainly as ‘soil’, as something whose only characteristic is that it’s lying underneath everything else.

|

| Automatically, I crept forward in a straight line until I bumped into a stump. Where was I actually going? Normally, I’m guided by trails in a pretty stilted process where I can either go forwards or back. Forwards is the goal and back is the opposite, like back to square one. Here, I could really go in all directions, except into the side of the stump. The openness made me dizzy. I was seeking a goal to crawl to because walking freely was too challenging. I decided on a thick beech tree about 10 metres away. Trees became resting points, perhaps because they were taller than me. |

|

| We humans are forward-looking creatures: our eyes look forward and our feet also face forward. We divide ourselves into a front and a back, and because we are three-dimensional, we have a side in between. There is a wonderful essay by David Borkenhagen, Octopus time, it’s called, where he shows how the way we move through space also defines our thinking, and particularly our perception of time. The future is ahead of us, the past behind us, or in some cultures the other way around. Our way of thinking about time is linear. And you cannot influence what is behind you. In the article, he asks how, if we moved like an octopus, our thinking about time would change, and with it, our perception of it. |

|

| An octopus has eyes on the side of its head, which it can turn so that its vision is 360 degrees. It has tentacles on all sides, giving its body the same reach on each side. Perhaps as humans we might allocate a front or back side to an octopus from sheer force of habit, but its body actually has no blind spots. An octopus interacts with everything around it. It lives in the sea, which means it can also move freely up and down: it is literally oriented to all directions. |

|

| If embodied interactions with our surroundings ground human metaphors for time, one can only imagine the metaphors an octopus might use. Given it has equal competence interacting with objects behind or in front of its body, past events could be, metaphorically speaking, just as manipulable as future ones. Expressions like ‘let’s put the past behind us’ would be meaningless for the octopus. |

| Octopus time is like a sea that you can move freely through. |

|

| The tree I was on my way to was much further away than I thought. Or, put another way, what I would normally call ’close’ is quite far away when my body is crawling. Subconsciously, I had estimated the time to the tree, and I only found that I’d made this estimate when it turned out to be completely wrong. I was much slower than I’d usually be, and on top of that, I was experiencing a lot of things along the way for the first time in my life. The more first times there are in a period of time, the longer that period of time feels. Both clock time and experience time are stretched. |  |

|

|

| Even before I reached the tree, there was something that smelt like a stable. I scoured the ground for animal poo, but it turned out I was smelling the animal itself. First there was a rustling and then a deer appeared. I held my breath and stood frozen to the spot. The deer quietly continued about its business, which was eating low-hanging leaves. It must have known I was there, because if I was smelling it, then it must surely be smelling me. I’d also been creating a lot of rustling as I moved and I wasn’t exactly camouflaged. But it apparently didn’t feel threatened, because it kept walking and eating quietly until it disappeared behind some bushes again. I’d never experienced something like this before. The deer in this forest always stiffened as soon as they caught sight of me. But the situation had turned on its head because now I was the one standing stockstill and the deer was in charge. How could that be? |

|

| It must have recognised me as human, I assumed I wasn’t fooling it by grovelling. Perhaps it noticed that my energy was different, that I was more open, and how well I was tuned into my surroundings. I had to be, because I’d shed my usual I-know-what-the-world-is-like convictions. I could never be the enemy, I was so at one with nature that the animals fully accepted me as one of them. |

|

| All this went racing through my mind, but if I’m honest, I don’t know anything at all about how deer see things or how their perception of enemies works. |

|

| Apparently, deer are constantly anxious. I read that in Being a beast (2017) by Charles Foster. Foster is a writer, ethicist and, more than anything, I would call him an adventurer in the consciousness. He describes how he tried as radically as possible to live the life of a red deer, as well as a badger, an otter, a fox and a swift. This led him into situations that would be foreign to the ordinary person and sometimes resulted in some spectacularly gross prose. For example, when he writes about how, as a badger, he lived in a burrow for three months and ate worms: |

|

|

|

| Worms taste like slime and soil. They are the ultimate local food and have, as wine connoisseurs would say, a distinct terroir. (...) Worms from Chablis have a long, mineral finish. Worms from Picardy are musty; they taste like rot and chopped wood. Worms from the Kentish Weald taste fresh and uncomplicated; they would go so well with fried sole. Worms from the Somerset Levels taste very strong and not very elegant, of leather and dark beer. (…) The worm’s body has the strongest taste. The mucus tastes different from the body. In fact, its flavour doesn’t even seem to have any connection with its terroir. Suck the mucus off and you find that Chablis mucus, at least in spring, tastes like lemongrass and pig shit, and Weald mucus like burnt flax and bad breath.

|

|

|

| And so it continues. Foster tries to convert all these sensory discoveries into language as exactly as possible. As an otter, he tried to catch fish with his hands at night, as a fox he would lie for hours in London backyards, sometimes in his own urine, as a red deer he would allow bloodhounds to hunt him and much more. Sometimes he arrived at completely new observations, and it also became insightful about the limits of human ability and perception. |

|

| It turns out my crawling through the forest is part of a tradition. The artist Thomas Thwaites also did a similar experiment. He built an exoskeleton, forcing his own body into the form of a goat’s, and tried to live with a herd of the real thing on an Alp. He only lasted a short time, because he developed an upset stomach because of the grass. |

|

| I wasn’t aware of this as I made my way through the forest. I was especially curious about the new reality I was creating in this way. Unlike Foster and Thwaites, I wasn’t emulating an animal, but I was perceiving the world around me completely differently. By going to the forest and physically changing to an unusual position, the hierarchy of my senses changed. My eyes gained a different, lower perspective, with less of an overview. I was much more aware of my environment now, through my sense of touch, my hands and my knees. The special thing about touch is that in the process, you feel the world as well as yourself. Now that I was seeing less with my eyes, I myself came into focus much more. It was very intimate. |

| In my new world, the ‘view’ was mainly defined by the ground. There were more smells down there than when you were up high, in the air. I already mentioned the tantalising earth, but there was much more such as mushrooms, the smell of decayed wood, leaves, I think I could even smell insects. And because I was afraid of being caught, my hearing was also keener, extending my world far beyond the limits of sight, smell and touch. The forest grew more alive, more charismatic, because I let it enter through many more channels. |

| I wonder how the world would enter into me if my senses were somewhere else entirely, or if there were even different senses. There are animals with eyes on their genitals, ears on their knees, noses on their limbs and tongues all over their skin. Ed Yong writes about it in An immense world. How animal senses reveal the hidden realms around us (2022). In the opening chapter, as a thought experiment, he gathers a variety of animals and a human, Rebecca, in a gymnasium. He describes how all these creatures perceive each other and the space differently, depending on what matters to their survival. |

|

|

|

| The elephant raises its trunk like a periscope, the rattlesnake flicks out its tongue, and the mosquito cuts through the air with its antennae. All three are smelling the space around them, taking in the floating scents The elephant sniffs nothing of note. The rattlesnake detects the trail of the mouse, and coils its body in ambush. The mosquito smells the alluring carbon dioxide on Rebecca’s breath and the aroma of her skin. It lands on her arm, ready for a meal, but before it can bite, she swats it away – and her slap disturbs the mouse. It squeaks in alarm, at a pitch that is audible to the bat but too high for the elephant to hear. The elephant, meanwhile, unleashes a deep, thunderous rumble too low-pitched for the mouse’s ears or the bat’s but felt by the vibration-sensitive belly of the rattlesnake. Rebecca, who is oblivious to both the ultrasonic mouse squeaks and the infrasonic elephant rumbles, listens instead to the robin, which is singing at frequencies better suited to her ears. But her hearing is too slow to pick out all the complexities that the bird encodes within its tune.

|

|

|

| A wonderful collection of animal senses comes through in the book: embryos of red-eyed macaques have vibration sensors in their inner ears that allow them to very precisely discriminate benign from malignant surface vibrations; bumblebees can detect invisible electrical halos around flowers with electroreceptors on their hairs; and the crest of female peacocks is connected to a nerve, allowing them to sense the air disturbances caused by the tail of a courting male. |

|

| Reality is shaped by the physical capabilities of the senses, and for every being there is a whole lot that goes beyond that. Zoologist Jakob van Uexküll in 1909 called this the Umwelt, the perceptual world of an animal, i.e. what your perception of the environment is. |  |

| In any case, it’s a real miracle that the sense of a coherent world emerges from things like waves of light and sound, vibrations, textures, chemicals, and magnetic and electric fields, because that is actually what is there. Everyone converts those stimuli into information through their senses and brains in very different ways. My world is one among many. |

When my alarm clock beeped, I was shocked. For a moment, I couldn’t remember what the sound even meant. Until I realised that my hour spent crawling was now over. Far too soon, I stood up. It was like my brain had already reset to thinking the way I would in regular life, but the rest of me hadn’t yet. My new balance was wobbly, the only tangents to the ground were my two thirty-by-10-centimetre soles of shoes, and with these, I held up the string that was me. The relationships I’d made with the forest in the past hour dangled down from my body like limp cords, and I’d pulled them loose by standing up so suddenly. The visual recording machine at the top of me became more active again: could I see the way I needed to go? Were there any people? There was nobody. I walked towards the path that would take me straight home. Through my soles, I could hardly feel anything from the ground. A drop of rain fell on my nose. The breeze caressed my cheek. The air didn’t hold any scents in it. Was this it then?

| When I stepped back into my parents’ house, they asked what was wrong. I looked different. I didn’t tell them, I wanted to find the right words for what I had just experienced first. I didn’t want to create a narrative that didn’t do justice to the experience. Some stories are well and truly less valid in others’ eyes, and actually in my own eyes, than others.

|

| Talking about my experience of the forest and myself crawling felt like it needed delicacy, and being as precise as possible about it was an almost political act. What was at stake was a whole world, an Umwelt, produced by my particular perception system: a body with human senses with a particular biology, which travelled through the world by crawling, causing my senses to obey a different hierarchy than usual. Attached to that was my own specific mind that continued to recreate the world for me from all the information that flowed in, through a filter of largely subconscious narratives. This last filter also made my experience in retrospect feel "fun, a bit strange, playful" and the world that emerged as less real than how I usually see it. |

’As if we do not hear from the whole, through bone, skin, nervous system and immaterial sensualities,’ says researcher and writer Sarah Amsler in a wonderfully astute article about how subconsciously we actually work with our perceptions. On the whole, we could do a much better job of listening to what flows into us than we generally do. Being truly open to the world around us, she says, goes far beyond what our five senses produce separately. We do this using our whole being, through our bones, skin, nervous system and ’immaterial sensualities’, by which she means something like a spiritual body. I can’t grasp that with my head, but I think that’s exactly the definition of it.

As far as I’m concerned, the credo ’see it and believe it’ ought to be consigned to the dustbin once and for all. The believability of what I think I see hinders the rest of my perception. Not only that: beyond the scope of my perception lie countless other worlds. I can understand something of that by studying other beings. But above all, I have to trust my new knowing. It’s the opposite of conventional science: knowing comes first, from that comes openness, at which point all observations that lead to a conviction of how the world is may dissolve.

| Quotes in their original language: |

|

If embodied interactions with our surroundings ground human metaphors for time, one can only imagine the metaphors an octopus might use. Given it has equal competence interacting with objects behind or in front of its body, past events could be, metaphorically speaking, just as manipulable as future ones. Expressions like ‘let’s put the past behind us’ would be meaningless for the octopus.

|

|

From: ‘Being a beast’, from the chapter of the badger. I don’t have the original text, but it must be in the book store.

|

|

The elephant raises its trunk like a periscope, the rattlesnake flicks out its tongue, and the mosquito cuts through the air with its antennae. All three are smelling the space around them, taking in the floating scents. The elephant sniffs nothing of note. The rattlesnake detects the trail of the mouse, and coils its body in ambush. The mosquito smells the alluring carbon dioxide on Rebecca’s breath and the aroma of her skin. It lands on her arm, ready for a meal, but before it can bite, she swats it away – and her slap disturbs the mouse. It squeaks in alarm, at a pitch that is audible to the bat but too high for the elephant to hear. The elephant, meanwhile, unleashes a deep, thunderous rumble too low-pitched for the mouse’s ears or the bat’s but felt by the vibration-sensitive belly of the rattlesnake. Rebecca, who is oblivious to both the ultrasonic mouse squeaks and the infrasonic elephant rumbles, listens instead to the robin, which is singing at frequencies better suited to her ears. But her hearing is too slow to pick out all the complexities that the bird encodes within its tune.

|

|