by Andy Merrifield

In November 2022 Andy Merrifield was invited by Østfold Internasjonale Teater curator-producer James Moore to be a critical friend during a weeklong artistic laboratory. The lab included a two-day professional seminar entitled IN SITU Focus 2022. Participating IN SITU artists were Johannes Bellinkx (BE), Eva Bubla (HU), Leonardo Delogu (IT), Seth Honnor (UK), Emke Idema (NL), Alexandros Mistriotis (GR), and Nana Francisca Schottländer (DK). Participating IN SITU partners were Kees Lesuis (Oerol Festival, NL) and Katrien Verwilt (Metropolis, DK). During the seminar Merrifield was asked to reflect upon the concept of Spatial Conciousness from various perspectives. He was then asked to write an essay regarding the theme and in the context of his experience as a critical friend through the course of the exploratory laboratory activities. He chose a letter from format.

---

The IN SITU Focus Seminar is a professional gathering for artists, professionals and actors of civil society which took place in November 2022 in Fredrikstad.

Participants questioned the methodology and possibilities around the development of a pilot event transcending the notion of festival and directly tackling the challenges of our contemporary society.

The idea of spatial consciousness stands at the heart of the conceptual approach advocated by James Moores – curator-producer for Østfold Internasjonale Teater - and here, Andy Merrifield - English writer and urbanist - dives into the roots of this philosophical and artistic perspective.

The task of the writer is by nature a solitary existence. Just before he died in 1985, the Italian novelist Italo Calvino meditated on this notion of the solitary writer. He knew that writing meant hours alone, necessitated a temperament marked by Saturn: introverted, melancholy, contemplative. Without the fixed gaze on “the immobility of silent words,” says Calvino, it’s hard to imagine how literature could ever get created. And yet, Calvino also recognises that literature isn’t quite as straightforward as that. Words are about communication, about exchanges with audiences, about dexterity and lightness, about engaging with the self in the world. The writer thus inevitably has a shadow figure: the spirit of Mercury.

Mercury is the god of communication and mediation, has winged feet, is light and airborne, agile and adaptable. Mercury is astute at establishing relations between the gods, between objects of the world and thinking subjects, developing exchanges between people and their desires. “What better patron could I possibly choose to support my proposals for literature?” Calvino asks. “My cult of Mercury is perhaps merely an aspiration,” he laments. “I am a Saturn who dreams of being a Mercury.”

So, when my friend James Moore from Norway invited me recently to participate in a week-long artistic laboratory, an experimental workshop alongside international artists, local partners, and critical friends, he’d prodded my Mercurial self. After months of COVID lockdowns and Saturnine solitude, it was time get airborne again, to float away with winged feet, to engage with people and ideas in person.

| James is curator-producer with the Østfold Internasjonale Teater in Fredrikstad, a city of 83,000 inhabitants, 20 kilometres from the Swedish border and 100 kilometres south of Oslo. Fredrikstad straddles the river Glomma and used to have a thriving sawmill industry —once bearing the epithet “plank town”—with a timber-exporting harbour and shipyard of national significance. Much of this heavy industry has now disappeared, and Fredrikstad, like a lot of contiguous towns, has been transformed by deindustrialisation. Future livelihoods and lifestyles are increasingly uncertain, particularly against a backdrop of ominous climatic change and environmental degradation. (Fredrikstad is adjacent to the 354 km2 Ytre Hvaler National Park, of which 340 km2 is under water; marine biodiversity there is rapidly declining.) |

| James is very interested in how this process is unfolding. His ambition is for public art not only to confront these transformations, but also to be itself transformative, formulating grander visions of a utopian future. “How may art in, of and for public space,” he wonders, “be a catalyst for new perspectives as society confronts existential challenges of increasing complexity? How might artists engage and involve inhabitants in the creative development and implementation of innovative and unpredictable works? How may selected places in and around Fredrikstad serve as context and material for meaningful artistic expression?” | |

| Østfold Internasjonale Teater (ØIT) handles a broad range of art, both on and off stage. It is Norway’s sole regional theatre devoted to airing site-specific theatre, as well as art in public space, organising workshops, seminars, and lectures, offering artistic residences for visiting creators and performers. In their latest venture, they’ve brought together seven artists from Denmark and Greece, Hungary and Italy, the Netherlands and the UK, all belonging to the IN SITU network, to dialogue with one another, inviting each to develop installations in and around Fredrikstad’s public realm. Indeed, these artworks will seek to enliven and enrich some of the town’s duller and emptier public spaces and landscapes. It’s a tall ask for the concerned artists. And it’s early days in project development. As such, the week-long laboratory is more a focus on questions and methods, on identifying possibilities and challenges, on being agile and adaptable like Mercury. | ||

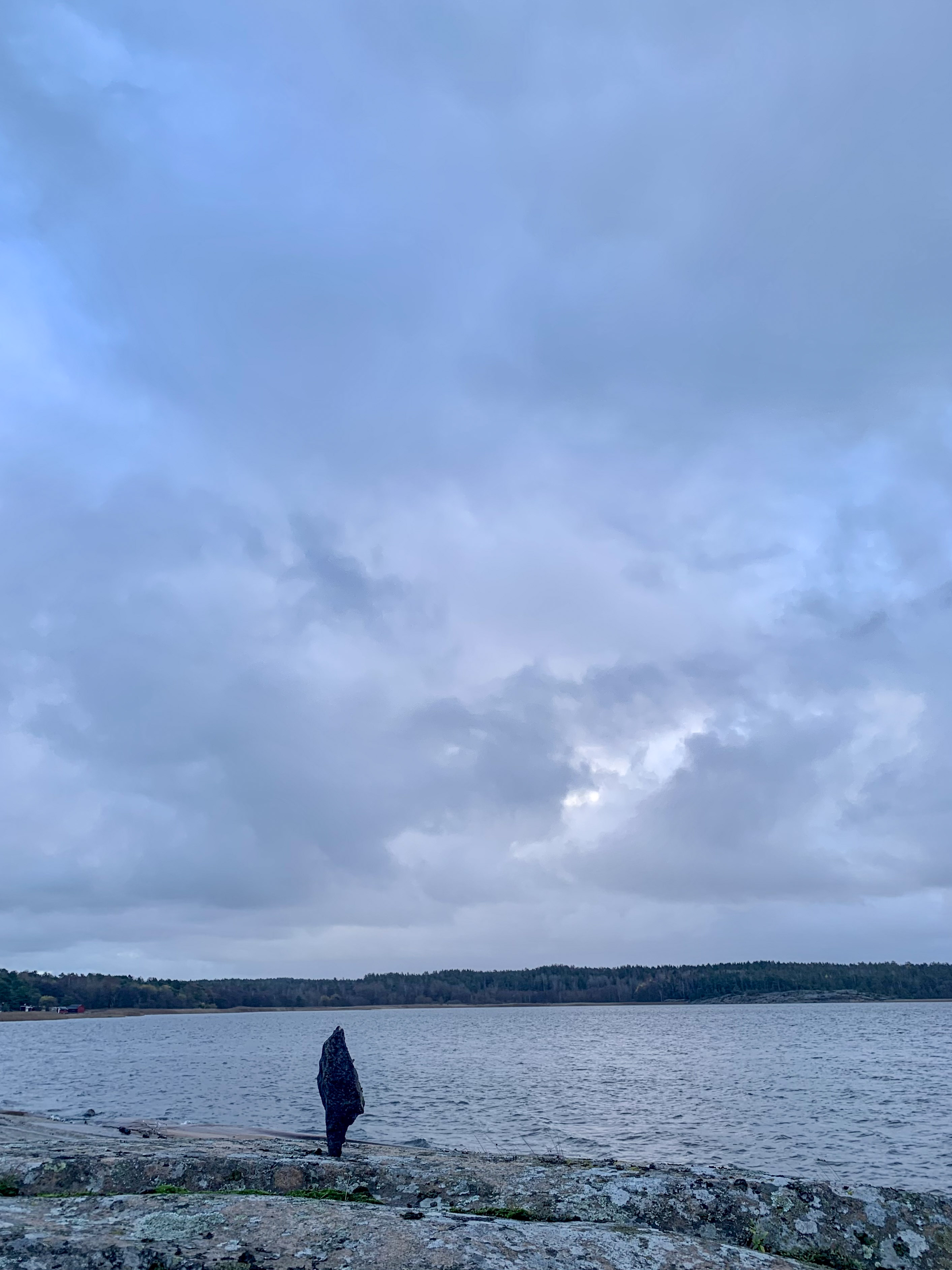

After all, the art itself here is Mercurial. It will appear and then disappear with the unbearable lightness of having been. Will it leave its trace? We’ll have to see. None of this art will be precious: we’re not talking about anything hanging on the walls of a bourgeois museum. This is public installation art, raw and in your face, questioning how to cultivate a fallow field on the edge of town, how to reconnect people with nature, link organic and inorganic matter. This is art that builds arches that will deliberately crash down, an art that harks out in the public square, that walks backwards, that tells you the time of day, that reveals what’s invisible in the visible. It’s an eco-sexual art, broadcasting poetic words while swaying in the breeze, having naked human bodies meld with landscapes, with sludge and toxic waste. It’s an art of the throwaway and readymade, of hydroelectric power stations and recycling plants, of quarries and pits, of stone and water, of happenings at the beach and in the city. It’s an experimental art that invents things we’ve hardly yet dreamt of.

James and ØIT have assembled a motley crew of artists who’ll create culture through disruptive imagination, an imagination around what space is and might be. Maybe it’s no coincidence that one of James’s favourite books is Lewis Hyde’s Trickster Makes This World (1998), a tale of thinking outside the box, of a mischievous boundary-crosser who operates somewhere in-between. James himself was born in Chicago, studied theatre in California, and still retains a U.S. passport. Yet he’s spent almost half his lifetime, the past twenty-five years, living in Norway. Now, neither American nor Norwegian, operating in the interstices of both identities, he takes inspiration from Hyde’s trickster artists who anoint themselves as “jointworkers”—“artus-workers”—as people who loosen things up where they’ve begun to stick or stiffen. Tricksters relish flexible and movable joints (the Latin root of artus is joint, as in articulate; not so much in speech but in joining bones together, like an artisan, a joiner of things). In this sense, tricksters are joint-disturbers. They work away at disjointing, rejointing and rearticulating, and this is what he and ØIT are trying to achieve in an unlikely Fredrikstad. They especially want to work away at the joints in a 30-kilometre radius they’ve traced around the city, a “circular frame” containing stiffing articulations between natural landscapes and industrial wastelands, between urban centres and agricultural peripheries. It’s a contrasting and complex biosphere that’s interwoven yet somehow arthritic. I’ve been asked me to come along and observe this grab-bag of tricks, to schmooze with the artists and their ideas, to be a “critical friend.” Specifically, the theatre wants me to share my insights around space, to talk to everybody about “spatial consciousness,” a sensibility that seems to underwrite much of the art and artistic performance getting proposed. What might all this lead to? Nobody is sure yet. Maybe a tri-annual festival in Fredrikstad, an alternative cultural encounter, beginning with a pilot event in 2024, inaugurating a longer-range ambition that reimagines how a “festival” might respond to the many challenges of our desperately troubled age.*** | ||

| When I wrote my PhD in Geography in the late 1980s, “space” wasn’t a very sexy subject. It wasn’t trendy like today. Few people really got what you meant by space. Outer space? The space of the planets, of the heavens, an astronomical space? Trying to explain my thesis on “social space” was always a source of popular amusement. Even the discipline of Geography was eyed with incredulity, seen as a poor relation alongside its prouder peer, History. History is the mover and shaker, an active moment in the passage of civilization. The march of humanity is the march of History. Geography is passive, not terribly important. It’s like watching a play at the theatre. The script, the action, the movement, all the comings and goings of the cast, the drama itself, that’s History, something dynamic. Geography is staging, mere backdrop, static, of little concern in itself. |  | |

This downgrading of Geography was worse in critical circles. We know how maps underwrote Empire, plotted and navigated global routes to plunder human and physical resources; that Geography, as a scholarly subject, has a few imperialist and colonialist skeletons in its intellectual closet; maps were power, are power, sources of military and financial power, guides to invade, to expropriate, to fence off. It’s hardly surprising that the Marxist tradition should be wary of Geography and dominated by historians. What’s odd, though, is why these historians should be so blind to spatial issues, conceptualising the laws of motion of capitalism as first and foremost temporal, as a capturing of surplus labour time. “Time is money,” says the old business adage. But so is space. From this standpoint, it’s as if capitalism has evolved on a pinhead, has decoupled itself from space.

The relativity of time and space is now widely acknowledged as the narrative of human life on earth. Einstein knew this was the law of the cosmos. We know, too, how bodies are shaped by the passage of time and by their relationship to space, to what surrounds us. In a curious way, rather than time assuming priority, we could even say that it’s the other way around: we live in time yet know it only through space. Clocks are objects in space, preeminently spatial objects, and the movement of time is inextricably spatial: needles moving on a dial, sometimes without figures, since we implicitly recognise spatially what time it is. Ditto in nature, where time is apprehended within space, by the movement of the sun above the horizon, its position geographically, the orbit of moon and the stars in the heavens, the localised nature of natural time. Time, in short, is inscribed in space. What better example is a tree trunk, whose lifeline we see if it’s hacked down, with its palimpsest of rings, marking eons of time, years of growth, time represented through space. What time is it? we ask. Never what space is it? | ||

| Spatial consciousness must conceive how space itself is conceived, how it is conceptualised by planners, architects, urbanists, bureaucrats, and technocrats. Lefebvre wants us to problematise how people with power and wealth conceive reality, how they envision the world we are compelled to live in and develop spatial practices around. This, in a nutshell, is what The Production of Space is trying to figure out: how different slices of spatial reality coexist and conflict. All of us somehow produce, perceive, and live out space, he says; yet all of us don’t make and live out that space in the same way or on equal terms. The perceived, the lived, and the conceived coexist as a “triad,” he insists, as a “trialectic,” a dialectical relationship between three aspects of the same space. This is where Lefebvre, the trickster, enters the fray, Lefebvre the “joint-disturber,” loosening the complex contradictions and articulations between and within space, between what’s perceived and practiced, practiced and lived, lived and conceived. |

***

But there’s another element to Lefebvre’s trickster imagination: a belief in the transgressive nature of art, that art can enlighten our knowledge of space and disrupt our practices in space. One of Lefebvre favourite slogans about art comes from Paul Klee: “Art does not reflect the visible; it renders visible.” Klee’s own art was obsessed with questions of space, with understanding lines and proportions, planes and dots, figures and objects connected or disconnected in time and space. Art lets us glimpse a spatial world beyond sight, says Klee. It offers us a ticket to ride, he says, “a little trip into the land of deeper insight, following a topographical plan.” He wrote these words in a brief essay, read by Lefebvre, called Creative Confession (1920).

"Art can enlighten our knowledge |

In it, Klee says modern art has moved away from objects in space to the very concept of space itself. It inaugurated a dramatic shift in spatial consciousness, and to a large degree Lefebvre’s Production of Space mirrors this shift. Listen to Klee explain what a new spatial consciousness entails: “A sailor of antiquity in his boat, enjoying himself and appreciating the comfortable accommodation. Ancient art represents the subject accordingly. And now: the experiences of a modern man, walking across the deck of a steamer:

1. His own movement;

2. The movement of the ship which could be in the opposite direction;

3. The direction and the speed of the current;

4. The rotation of the earth.

5. Its orbit;

6. The orbits of the stars and the planets around it.”

Henceforth a whole new reality starts to oscillate before us.vaster and multidimensional, dynamic and vibrating, pushing and pulling us in opposite directions, full of contrast and contradiction, just like life itself, just like space itself. Klee thinks abstract art can create illusory states that “somehow encourage and stimulate us more than the familiar natural state.” The best art forms, he implies, have a double consciousness: they’re renderers of the visible at the same time as they’re creators of the invisible, of the yet-to-be-imagined.

Something hidden is revealed and something new is created, something that didn’t exist before, whether painted on a canvas or installed in a street or field.

| Public art has a different reach to a sculpture or painting in a museum. For one thing, this art won’t be there forever; most will be assembled and later dismantled. It might not even be anything tangible at all, is more performative, purely ephemeral, occupying space, producing a space that has no intention of ever enduring. This is more the intent of ØIT’s chosen artists. Some of their art work is the art of taking a walk, leading audiences through city spaces, both strange and familiar, sometimes strangely familiar. The art of taking a walk is a peculiar form of psychogeography, a drift through varying landscapes, a sensibility that’s at once conceptual and affective, thinking and feeling one’s way through spatial ambiences, trying to understand presence and absence, why spaces feel right, why they work, and why others don’t, why something is missing. |  |

| If certain art walks, then other artistic performance talks, is about verbal expression, a poetry of place and sound, of space and language. This art offers a richer meaning to reading landscape as a text. Often, like space itself, language has been misused and abused, corrupted and fabricated by politicians and place-makers. The artistic response has been a sort of Neo-Dada spirit, reenergising what began in the 1916 at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire during the First World War: a shift away from the meaning of words to the meaning of sounds, an effort to free words from syntax. One of the Dadaists great inventions was the “sound poem,” phonetic verse that not only reinvented language but also reinvented movements of sound-bodies in space, instigating a kind of bodily onomatopoeia. The notion hasn’t been lost on some of ØIT’s artists who strive to reconnect bodies, words, and meaning with spaces that have lost meaning, that have had their meaning stripped of any human and post-human communication. |

| How all this art might come together in 2024, and what sort of public festivities and (UN)COMMON SPACES they might collectively engender, is still in the process of getting worked through. But the prospect of creating unpredictable art for an unpredictable public is an intriguing and exciting one, though likely a little scary for organisers and artists alike. Lefebvre himself knew about the vitality of festivals in democratic place-making, about how they could galvanise the country and the city, and collapse, if only temporarily, rural and urban divisions of labour. That’s assuming they don’t turn into purely commercial jamborees, great spectacles to exploit and promote the region economically. James has another concept of festival in mind, just as Lefebvre did. Lefebvre’s model was for reinvigorating the medieval festival, with its priority accorded to non-work, to unproductivity, to homo ludens, to people being at heart players not workers. |  |

Festivals, Lefebvre says, were “true spaces of pleasure,” cathartic emotional releases. Festival time meant spaces of song and dance, of play and laughter, of rowdy indulgence and over-indulgence. People dropped veils, stopped performing around labour, ignored authority, and simply let rip. Festivals tried to repair lost unity by re-establishing connections with the land, heightening an awareness of the seasons, of harvest time, of planting and sowing, of natural cycles, of nature and human nature, of all that was pleasurable around food and environment and communal life. Festivals recovered temporal cycles in space, Lefebvre says. Perhaps we need to see the IN SITU artists in Fredrikstad as part of a wandering medieval minstrel show, moving about from town to town at festival time, inside the circular frame, tricksters spreading the word, performance artists installing and reinstalling their works like some improvised traveling circus, repeating their art yet never repeating it in exactly the same way: artus-workers, disturbing joints as they go, shifting regional spatial patterns, loosening places and spaces of stiff articulation.